Caregiving Experiences of Latino Families With Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder

- Research

- Open up Access

- Published:

Listen the gap: an intervention to support caregivers with a new autism spectrum disorder diagnosis is feasible and acceptable

Airplane pilot and Feasibility Studies book 6, Article number:124 (2020) Cite this article

Abstract

Introduction

Children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) benefit when their caregivers tin finer advocate for appropriate services. Barriers to caregiver engagement such equally provider mistrust, cultural differences, stigma, and lack of knowledge can interfere with timely service access. We describe Listen the Gap (MTG), an intervention that provides educational activity near ASD, service navigation, and other topics relevant to families whose children accept a new ASD diagnosis. MTG was developed via customs partnerships and is explicitly structured to reduce engagement barriers (east.g., through peer matching, meeting flexibility, culturally-informed practices). We also present on the results of a pilot of MTG, conducted in preparation for a randomized controlled trial.

Methods

MTG was evaluated using mixed methods that included qualitative analysis and pre/postal service-test without concurrent comparison group. Participants (n=9) were primary caregivers of children (ages 2-7 years) with a recent ASD diagnosis and whose annual income was at or below 185% of the federal poverty level. In order to facilitate trust and human relationship building, peer coaches delivered MTG. The coaches were parents of children with ASD who we trained to evangelize the intervention. MTG consisted of upward to 12 meetings between coaches and caregivers over the class of 18 weeks. Coaches delivered the intervention in homes and other community locations. Coaches shared data nearly various "modules," which were topics identified as important for families with a new ASD diagnosis. Coaches worked with families to reply questions, set weekly goals, assess progress, and offer guidance. For the airplane pilot, we focused on three principal outcomes: feasibility, engagement, and satisfaction. Feasibility was measured via enrollment and retention data, equally well as bus fidelity (i.e., implementation of MTG procedures). Date was measured via number of sessions attended and percentage completion of the selected outcome measures. For completers (n=vii), satisfaction was measured via a questionnaire (completed past caregivers) and open up-ended interviews (completed by caregivers and coaches).

Results

We enrolled 56% of referred caregivers and 100% of eligible families. Retention was loftier (78%). Coaches could deliver the intervention with allegiance, completing, on average, 83% of plan components. Engagement likewise was high; caregivers attended an average of 85% of total possible sessions and completed 100% of their measures. Caregivers indicated moderately loftier satisfaction with MTG. Qualitative data indicated that caregivers and coaches were positive virtually intervention content, and the coach-caregiver relationship was important. They besides had suggestions for changes.

Decision

Listen the Gap demonstrates evidence of feasibility, and data from the pilot suggest that it addresses intervention engagement barriers for a population that is under-represented in research. The results and suggestions from participants were used to inform a large-scale RCT, which is currently underway. Overall, MTG shows promise equally an intervention that can be feasibly implemented with under-resourced and indigenous minority families of children with ASD

Trial registration

This study is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03711799.

Introduction

Family Date: Benefits and Barriers

Engaging children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in early intervention improves child and family outcomes. Early intervention can maximize long-term outcomes; it therefore is critical that parents learn almost and admission services equally soon as possible [1, 2]. Considering children with ASD ofttimes admission services across a range of providers and service systems, their caregivers oftentimes have substantial care coordination responsibilities [three]. Many studies have highlighted the difficulties families confront in navigating the complex service systems for ASD [4], leading to negative outcomes. For case, Brewer [five] found that mothers reduced their paid work to meet the demands of accessing ASD-related services. The author highlighted the disproportional effects this has on parents from depression-income households.

Delays in service admission are peculiarly common amongst families from traditionally nether-resourced groups. Children from racial or ethnic minority groups are less likely than white children, and children from depression-income households are less probable than higher-income children to be diagnosed with ASD at an early historic period [vi, 7]. They are besides more probable to kickoff services at an older age and receive fewer services [6, 8]. Parents who are struggling financially oft report limited guidance on steps to accessing services, and have identified a number of structural barriers (due east.thou., work schedule or transportation) to meeting their child'due south needs [9, ten]. Many parents feel overwhelmed with managing their child'due south support needs in the context of financial instability, stigma surrounding ASD, and isolation [11, 12]. Maybe every bit a effect of challenges in navigating service systems, parents of children with ASD oft experience more stress and mental health problems than parents of children with other disabilities or typically developing children [13,fourteen,fifteen]. Parents of children with ASD also written report that they do not understand the service options available to their child [10]. This is an important consideration, as parents' service noesis appears to be more than of import than socioeconomic condition per se in predicting their children'south service use [ix].

Some other gene that may limit service engagement for depression-resource families is their distrust of the medical arrangement [sixteen], based on negative experiences or mismatched cultural behavior. Distrust of the service organisation is exacerbated past poor communication about diagnosis and handling, inadequate access to treatment, and limited interest of parents in decision-making about services [17,18,19]. For case, parents have reported that their children's needs can become secondary to the battle over the cost of intervention and provider preferences for certain interventions [18]. Further, interventions for children with autism often are non culturally sensitive in a way that meets the needs of parents of color or under-resourced families [xx, 21]. This cultural mismatch can result in underuse of services and low treatment adherence [21]. Therefore, the institution of collaborative, supportive programming between parent and therapists/educators who are culturally competent and able to provide a variety of resources to economically diverse families is of utmost importance [ten, 22].

Addressing Engagement Barriers

Interventions designed to increment caregiver'south cognition and advocacy take been successful for parents of children with ASD both as standalone interventions [23] and as components of more wide parent grooming [24]. 1 culturally inclusive parent intervention model for children of color involves using peer-mediated models, such every bit the Promotora de Salud Model. In peer-mediated approaches, individuals – such every bit lay community health workers – deliver interventions for parents that are culturally relevant and based upon shared experience [25]. Rather than representing a single type of intervention, peer-mediated intervention is an arroyo to delivering prove-based information and services. Information technology has been used to back up Latinx families of children with ASD, with promotoras coming together with parents weekly in their homes. Preliminary evaluations suggest that this model is effective in increasing parent noesis and access to community resources [26]. Farther, the utilise of peer coaches to deliver interventions to parents has been identified as a critical element in increasing parent engagement in their child'south treatment [27]. These findings suggest the importance and promise of parent-centered interventions that are focused on service access and delivered by trusted peers with similar life experiences [10].

Community Partner Input

Interventions that include partnership with key customs stakeholders tin can upshot in more than positive outcomes and more successful implementation than those that practice not involve community appointment [28]. We developed the intervention described in this pilot written report using an iterative community-partnered approach that incorporated stakeholder feedback and an in-depth exploration of the barriers to treatment appointment for nether-resourced and minority caregivers of young children with ASD. Consequent with previous literature, caregivers reported organisation-level concerns (e.g., confusion around navigating service systems and a desire for greater support) and barriers related to cultural identity (due east.1000., community stigma, experiences with provider discrimination, express linguistic communication accessibility). They as well wanted connection and guidance from others with similar life experiences [ten], similar to the findings described in studies of peer-mediated models. These findings guided the evolution of our intervention – Listen the Gap – designed to explicitly address barriers to treatment engagement for under-resourced and minority caregivers of young children with ASD. In this written report, we used a peer-mediated model to deliver Mind the Gap, which was a packaged intervention based on show-based data.

The Present Study

Mind the Gap is a flexible, caregiver-focused intervention for families of young children with ASD. It addresses issues salient to caregivers (e.grand., social support, system navigation, ASD knowledge, stress direction) and children (e.g., challenging behavior, communication, service access) to support families in quickly accessing community services. Consistent with models using peer coaches with shared experience, our coaches were other parents of children with ASD, who are likely to engender trust with parents of newly diagnosed children based upon shared experience. The goal of Listen the Gap is to engage caregivers of immature children with ASD to increase service use. Nosotros adult Mind the Gap using principles from the RE-AIM framework (Reach, Efficacy, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance) [29], which aims to shut the inquiry-to-do gap by developing interventions with both the participants and settings represented at each stage, and planning for and gathering information on implementation from the first [30].

In grooming for a large-scale evaluation, we conducted a pilot written report (due north=9); our aims were to evaluate: 1) the feasibility of Heed the Gap commitment; 2) preliminary caregiver engagement outcomes; and 3) the feasibility of collecting outcomes data about caregivers. These aims are consistent with the Achieve, Implementation, and Adoption phases of the RE-AIM framework. Information from this pilot supported a randomized controlled trial of Mind the Gap and informed intervention refinements for the full trial. An RCT designed to provide information on Efficacy, Implementation, and Maintenance is underway.

Method

Design and Setting

Nosotros used a mixed-methods approach that included qualitative assay and a pre/post-test study design without concurrent comparison group. We recruited participants from four sites: Los Angeles, CA; Sacramento, CA; Philadelphia, PA; and Rochester, NY. These sites comprise the Autism Intervention Research Network on Behavioral Health (AIR-B), a federally funded research network dedicated to improving outcomes for children with ASD and their families who experience income-based disparities. Nosotros therefore engaged with communities that included high rates of families living at or about the poverty line. Local Institutional Review Boards at each participating site approved the report procedures, with UCLA as the IRB of tape (IRB# 17-000029). Although no changes to the pilot methodology were made during the trial, we tracked opportunities for refining the methods for the RCT phase. The length of the pilot was delineated as ane yr, to permit for completion of all intervention and cess prior to the initiation of the RCT.

Recruitment and Participants

Caregivers

Participants included primary caregivers of children betwixt 2 and 7 years of age that received a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder within the concluding year (northward=9). From Apr 2016 through July 2016, each site attempted to enroll two or 3 families; this sample size allowed for sufficient piloting of the intervention methods to identify needed modifications for the RCT. Inclusion criteria were: ane) the kid could non be receiving any autism-specific services (e.thou., high-intensity practical beliefs analysis or special instruction,); 2) the family'south annual household income had to be at or below 185% of the federal poverty level; three) the caregiver had to speak English or Spanish; and 4) the caregiver was willing to participate in the intervention for 12 weeks. Income criteria were set up based upon the written report aims of evaluating an intervention focused on reducing engagement barriers for under-represented families. There were no exclusion criteria regarding the kid's intellectual performance, autism severity, advice skills or comorbid conditions. Caregivers could not participate if the kid was in an out-of-home placement.

Sites engaged local customs partners to identify viable streams of recruitment and create a system for processing referrals. Referrals came from local pediatrician offices, early intervention agencies, developmental behavioral pediatric clinics, local community organizations, family unit resource centers, and schoolhouse staff. Caregivers could self-refer from posted recruitment flyers and social media. Research staff contacted interested families to provide more than information and assess for eligibility.

Peer Coaches

Peer coaches (n=12) were recruited through partnerships with community organizations for participation in this airplane pilot and the larger study. Each site recruited more peer coaches than needed to provide sufficient opportunities for cultural matching with participants. Sites worked with their local community partners to market the opportunity to parent and advancement groups. Other recruitment methods included social media ads, and recruiting through providers from community clinics. Peer motorbus eligibility included: one) having a kid age vi years or older with a diagnosis of ASD provided at to the lowest degree 3 years prior; 2) previous feel working with other parents and the service system in their area; three) fluency in English language or Spanish. Twelve parents participated equally peer coaches. The coaches were primarily female with an boilerplate of 3 years previous feel working with families.

Listen the Gap Intervention

Development and Structure

Nosotros developed Mind the Gap through an iterative collaborative process with community stakeholders. A modular arroyo provides opportunities to individualize the intervention based on each family's needs. Relevant topics were identified based upon data from focus groups [ten], customs partnership input, and from previous research. This study included seven modules (Table i), each of which consisted of short advisory videos, narrated PowerPoint presentations, infographics and other data sheets, and topic-related worksheets. In improver to didactic content, each module included appointment activities and goal-oriented tasks for the parent that the coach and parent identified together. The modules, materials, and videos were translated into Spanish.

Each caregiver was matched with i peer coach, who worked with the caregiver throughout the study. When possible, we matched caregivers and coaches on civilisation and linguistic communication, with the goals of enhancing their ability to develop rapport and maximizing the likelihood of shared experiences. Prior to starting the intervention, peer coaches participated in an intensive, 12-hour preparation on: ane) components of the intervention; ii) information collection procedures; 3) caregiver engagement strategies; iv) community research ethics; and 5) ensuring safe and boundaries with enquiry participants.

Intervention delivery

The intervention consisted of weekly meetings between peer coaches and caregivers; this phase lasted for 12 sessions, completed in up to 18 weeks to accommodate missed or cancelled meetings. Meetings could occur: 1) in-person, at the preferred location identified by the caregiver (e.grand., home, library, community middle), two) via secure Zoom teleconferencing; or 3) over the telephone. An initial in-person meeting between the caregiver and member of the research squad included: a) provision of consent; b) confirmation of community diagnosis; c) completion of parent questionnaires; d) optional enrollment in Parent Square (on on-line, secure communication system); e) review of the Heed the Gap materials binder; and f) provision of initial data almost the peer bus. Intake meetings (Session one) took place with the peer motorbus in a location convenient for the family. During the coming together, the peer coaches followed a semi-structured intake interview script to institute rapport with the family unit, learn nigh goals for their child and family related to ASD, and identify the family unit's basic needs. In subsequent meetings (Sessions 2-12), caregivers worked with their peer coaches to review relevant content and engage in an ongoing goal-setting process. Sessions occurred approximately every week by phone or in person, with the goal of at least i in-person coming together per month. Coaches followed a general session structure: a) reviewing progress since the previous session; b) profitable the caregiver in selecting a new topic to review; c) providing relevant information on the chosen topic (e.g., watching module videos, reviewing handouts, completing worksheets, providing resources); d) setting weekly adjacent steps and documenting them on the family'south handout; and eastward) setting the data and time of the next session. Family needs and preferences guided topic selection. Coaches and caregivers collaboratively reviewed progress each week, with coaches providing additional assistance to overcome barriers. While engaged in agile coaching, peer coaches participated in regular supervision meetings with study staff, who in plough were supervised by a licensed psychologist. Meetings involved a combination of education on identified topics (e.1000., caregiver engagement, cross-cultural communication), instance presentations, and group troubleshooting. If needed, the inquiry team assisted the peer coach by providing supervision, consultation, or admission to additional resources.

During intervention, peer omnibus/participant dyads could communicate via cursory phone check-ins or Parent Square. Parent Square is an application available in English and Spanish that participants could utilize to communicate well-nigh the intervention and share information and resources via straight messages, posts, creating events, etc. Parents and peer mentors received preparation in how to use the app. Three sites used Parent Square, equally the Rochester IRB did not approve its utilize. Coaches were encouraged to schedule meetings and share information through parent square, and to check the app for messages at least weekly.

Primary (Feasibility) Outcomes

Feasibility outcomes were fourfold. First, nosotros nerveless data on enrollment and memory (i.e., Reach ); enrollment was defined as the percentage of participants who were screened and determined eligible and who consented to participate. Retention was divers as the percentage of participants who completed intervention and data collection at exit. A recent systematic review of parent appointment in child-focused interventions [27] for under-resourced families reported mean retentiveness of 74%; we therefore aimed for over 80% retention.

Second, nosotros tracked intervention allegiance (i.e., Implementation ). The fidelity of peer coach implementation was measured through sound-recording and coding 25% of phone and in person sessions, as determined by an contained statistician who selected sessions using a random number generator. Following recording, a fellow member of the research team coded the audio for fidelity using the fidelity of implementation checklist. Based on fidelity conventions, we aimed for a benchmark of 80% allegiance.

Tertiary, we collected participant engagement information; this was a disquisitional dimension of the pilot as these data directly provide information regarding how well Mind the Gap addressed common obstacles identified in the literature, given that a major development aim in Mind the Gap was reducing barriers to handling engagement. We measured date in ii ways: 1) number of sessions attended and ii) digital engagement information on communication via Parent Square. User data was extracted from the app using R programming. Count data relating to app user activities, including posting, private message, comments and resource uploading activity, were calculated for parents and peer mentors. This was an exploratory measure, given that there is limited research on digital engagement in these populations for child-focused interventions.

Fourth, we assessed caregiver and coach satisfaction (i.east., Adoption ) with MTG, using mixed-methods. Although not a pure measure of adoption, motorbus satisfaction was used equally a proxy in this pilot, every bit provider (i.eastward., coach) satisfaction with an intervention would likely increase its uptake. Caregivers rated their satisfaction with the intervention on an 18-item Caregiver Satisfaction Survey, using a v-point Likert scale to identify their degree of agreement with various statements (higher scores indicate more positive perceptions). Items asked about structure and content of Heed the Gap (due east.thousand., "The topics we met covered my needs," "The number of sessions seemed nigh correct"). We aimed for families to point that they were mostly satisfied or better (i.e., average rating of 3.five or above). To supplement quantitative information, we nerveless qualitative data via a semi-structured interview on satisfaction administered to caregivers and coaches by members of the research team. To obtain full general impressions of the program, we asked open-ended questions near satisfaction with the intervention, the success of the relationship with the peer double-decker, and possible improvements to Listen the Gap. The information were and then coded and summarized into overall feedback on caregiver and double-decker satisfaction.

Secondary (Mensurate Completion) Outcomes

Participants completed self-report measures based on our theorized mechanisms of change. In the context of the pilot –and given the minor sample size – pre/post comparisons of the data is inappropriate, given express ability. Instead, secondary outcomes focused on completion of consequence measures. Specifically, documenting the ability to collect consummate data provides additional support for the feasibility of using these measures in a larger trial. We as well present the mean scores on these measures at baseline and leave, both to narrate this pilot sample and to provide context to the interpretation of the findings.

Caregiver Agency Questionnaire

The Caregiver Bureau Questionnaire is adjusted from Kuhn and Carter [31], and is a 10-item survey about how often the parent engaged in sure activities related to promoting child evolution. It yields a score range from 10 to 50, with higher scores being indicative of higher agency. While non yet a validated mensurate, an initial evaluation of caregiver agency has been conducted in parents of children with ASD [31].

Maternal Autism Knowledge Questionnaire

This ten item truthful/false questionnaire measures knowledge of facts about autism in the areas of diagnosis, symptoms, treatments and interventions, and etiology. It was adjusted from a longer version, with permission of the survey author [31]. The percentage of correctly answered questions constitutes the autism knowledge score.

Caregiver Stigma Scale

This is an xi-item scale adapted from an unpublished measure [32] that assesses the degree of stigma that caregivers have near receiving professional person services or treatment for their child from a mental health or developmental specialist (e.g. developmental pediatrician, psychologist, psychiatrist). It yields a score from xi to 55, with higher scores indicative of higher stigma.

Family Empowerment Scale (FES)

This is a 34-item measure out [33] that measures empowerment in families with children who have emotional, behavioral, or developmental disorders. The FES has three subscales, Family, Service System and, Social Politics. Higher scores are indicative of higher family empowerment.

Data Collection Procedures

Given the written report aims, chief outcomes were measured weekly, and secondary outcomes were measured at baseline and mail service-treatment. The schedule of measures was organized around information collection for both caregiver and peer coach participants (run across Table 2).

Information Drove Procedures for Pre/Post Measures

Caregiver participants completed baseline measures immediately following consent. Post-treatment information drove occurred inside two weeks of the last session (i.e., session 12); this time indicate included completion of all parent questionnaires from baseline, with the add-on of a parent Satisfaction Survey. Peer coach measures included the demographics questionnaire (baseline) and the feasibility interview (post-treatment).

Information Collection Procedures for Measures used within the Intervention

Peer coaches completed engagement information (i.due east., main consequence information) weekly based upon parent omnipresence at meetings, topics covered, and goals completed. To ensure consistent implementation of Listen the Gap procedures, treatment allegiance information (i.e., ratings of peer coach implementation) were nerveless for 25% of sessions, which were randomly selected and recorded during the intervention phase. Recordings were rated against a checklist of procedures that were required for each visit. Each session allegiance was calculated as a percentage of number of procedures completed by the coach divided by the total number of procedures. Total allegiance is expressed as an boilerplate of all coaches' session fidelity across sites.

Information Analysis

Descriptive statistics for both primary and secondary measures are presented below. For the secondary upshot questionnaires, participant baseline characteristics are represented past the hateful score on each questionnaire, also as rates of completion on each measure. Given the pocket-size sample size, comparative statistics were non conducted, as we would be significantly underpowered to detect changes.

Results

Participant Demographics

Table 3 shows demographics for caregivers, their children, and peer coaches. Caregivers were largely female person and Hispanic or Latinx; demographics were fairly as distributed across education and income. A third of caregivers spoke Castilian and received the intervention in Castilian. The mean age of the children was 2.5 years, and virtually were male. 5 caregivers were married or living with a partner and the others were either separated (22%), divorced (11%), or unmarried (xi%). All caregivers had an average income of less than $l,000 a year and brutal below the federal poverty level standards based on the ratio of income to the number of people in the household.

Feasibility outcomes

Enrollment and Retention (i.e., Reach ).

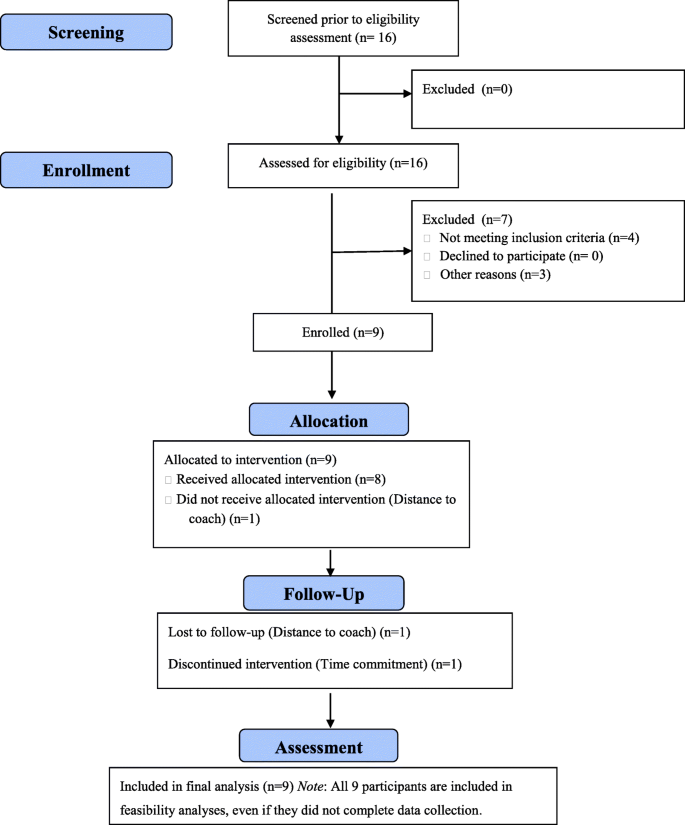

Referrals to Listen the Gap came primarily from customs diagnostic clinics and state-funded resource centers. Out of 16 total screenings, nine caregivers were eligible and subsequently recruited and enrolled across four sites (UCLA: 3, Penn: 2, UC Davis: ii and University of Rochester: ii) for the pilot written report (i.e., 56% enrollment of total referrals and 100% enrollment of eligible families; see Fig. 1).

Consort Diagram

There was practiced retention, with seven out of nine, or 78% of enrolled parents completing the twelve weeks of the intervention. One family withdrew from the study post-obit the intake session, due to the time commitment. The assigned charabanc to the other family had difficulty reaching them for coaching during the intervention stage (i.e., following intake), and the family unit was eventually lost to follow-up.

Omnibus Intervention Allegiance (i.due east., Implementation ).

Every bit rated past research staff, coach allegiance averaged 83% beyond sites, with private ratings ranging from 66% to 100%.

Caregiver and coach satisfaction (i.e., Adoption ).

Data from the Parent Satisfaction Questionnaire indicated moderate satisfaction with the Mind the Gap program (i.due east., an average of 3.ix points per item out of a possible 4.5 points), with scores ranging from ii.two to 4.v.

Qualitative interviews with coaches and parents indicated more often than not positive views toward most aspects of the intervention. Coaches reported that the training was helpful and that they benefitted from the support provided by the research team. Coaches also described the intervention technology as useful for sharing information and communicating with families. All coaches were greatly satisfied with the intervention content, including accessibility and helpfulness of the materials and modules, diversity and family unit centeredness of the topics, and the usefulness of the video modules. Both groups indicated a preference for a combination of in-person and phone meetings.

Parents and coaches described supportive relationships with each other. All parents mentioned that they were very happy with their coach, appreciated the relationship, and felt a sense of mutual understanding. Parents overwhelmingly viewed the coach as the most of import and helpful aspect of the intervention. They noted, however, that is would exist very important that caregivers and autobus be matched on personality, and that matches should be bundled based on location, condolement with technology, and communication way. Other constructive feedback from coaches included that the data forms were cumbersome and overwhelming, with suggestions for improving their ease of use such as combining some of the forms and making them shorter. Parents suggested increasing the length of the intervention to allow for a more extended intervention period and increasing the time between sessions from weekly to twice monthly.

Parent Engagement

Omnipresence

On average, parents attended ten of 12 sessions (85%). Most participants attended 12 sessions, just one family merely completed four sessions. Encounter Tabular array iv for a full clarification.

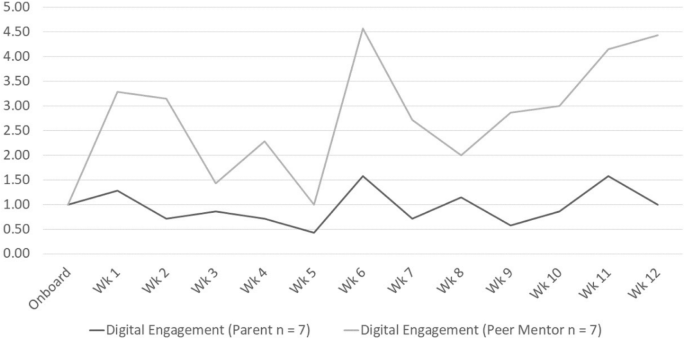

Digital Engagement

All parent and peer coach pairs successfully started Parent Square accounts (Fig. 2). Most participants used the app to communicate during the intervention (parents =71%, peer mentors = 86%) and follow upwards menstruation (parents =71%, peer mentors = 71%). College digital engagement occurred for both parents and peer coaches during the treatment period, with college peaks in week six and 12 for peer mentors and similar lower peaks for parents in weeks 6, 12 and 16. Declining digital engagement occurred for both parents and peer coaches throughout the follow upward period, with no participation after week 30 from either parents or peer coaches.

Within-Treatment Digital Date

Completion of Measures

All parents completed all measures at baseline (Table 5). All parents who finished Mind the Gap also completed these measures again post-intervention. All simply one participant completed the satisfaction measure at get out.

Parent Report Measures

Meet Tabular array 5 for a summary of the baseline and exit descriptive data.

Caregiver Agency Questionnaire

The mean baseline score on the Caregiver Agency Questionnaire was 40.half dozen, indicating high agency prior to intervention. Although the adaptation of the measure used in this study has not been normed, the baseline findings are similar to data obtained on the original Maternal Agency Questionnaire, which plant a hateful rating of 32 (out of a possible range of 10-50) among mothers of children with ASD [31]. Post-obit intervention, the hateful score reported was twoscore.4, with a range of 30-48.

Autism Knowledge Questionnaire

At baseline, caregivers answered an average of 73% of questions correctly on the Autism Knowledge Questionnaire, which was lower than the 91% reported by the original developers of the measures [31]. At go out, caregivers answered an average of 80% of questions correctly.

Caregiver Stigma Scale

Caregivers reported relatively high stigma at baseline (M=48.6), and stigma was similar at exit (1000=50.3).

Family Empowerment Scale

At baseline, scores on the Family unit Empowerment Scale savage at the moderate levels across subscales, with the Family (One thousand=48.seven) and Service (M=48.seven) subscales being somewhat higher than the Interest subscale (M=33.8). Of note, the ranges on the Service subscale narrowed from baseline (31-60) to get out (45-lx). The full baseline average of 131.i (range 101-162) was comparable [33] or slightly lower [34] than those reported in other samples of parents of children with emotional disabilities involved in navigating the service system. Post-obit intervention, caregivers reported a Total Score of 134.3 and a narrower range of scores (115-160).

Word

We used an iterative, community-partnered approach to develop a modular, peer-led service navigation intervention, Heed the Gap, designed to increase service admission for nether-served parents of immature children with ASD. In an try to improve the intervention'south ecological validity, stakeholder feedback guided the development of Mind the Gap to address barriers and capitalize on facilitators to service engagement [x]. In addition to community input, the intervention likewise drew from inquiry showing improved parent date when a peer with similar life experiences delivers the intervention [26]. The goal of this pilot report was to provide preliminary evidence regarding Mind the Gap's feasibility, acceptability, and efficacy, and to inform adaptations in preparation for a large multi-site randomized trial.

Users who notice interventions acceptable are more likely to implement them successfully and sustain their apply [35]. Mind the Gap demonstrated high acceptability from parents and peer coaches for content and commitment method. Parents as well reported that they felt more empowered and effective in navigating their kid'south treatment upon completing the intervention. Overwhelmingly, parents reported that the human relationship with their peer coach was the most essential and helpful aspect of the intervention. In follow-up interviews, all parents described a supportive relationship with their peer coaches built on trust and common respect. like those receiving other peer coaching interventions [26, 36], parents who received Mind the Gap valued the support of the peer coach above other aspects of the intervention, though it is unclear if access to the materials without peer coaching would have been sufficient to ameliorate family outcomes.

We assessed preliminary implementation outcomes for Mind the Gap using the guiding principles of the RE-AIM framework (Reach, Efficacy/Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance) [29]. Our preliminary findings indicate that Mind the Gap is feasible, and acceptable to both parents and peer coaches. A disquisitional aspect of an intervention'due south feasibility of implementation is its Accomplish, or the proportion of individuals who are willing to participate in an intervention [30]. The loftier rates of enrollment and retention of participants within this report, particularly those from under-resourced and ethnic minority groups who are ofttimes not represented in research, indicate that Mind the Gap is likely to have high Reach for families and children who are vulnerable to poor long-term outcomes.

We besides assessed Mind the Gap's Implementation, or the extent to which the intervention was delivered equally intended [30], by evaluating the peer coaches' intervention fidelity. Peer coaches accomplished adequate intervention allegiance, indicating that trained community providers tin can implement Mind the Gap as intended. The fact that intervention fidelity was high is notable given that the interventionists were new to research and were non clinicians. The RE-AIM framework defines effectiveness as the impact of the intervention on important outcomes. Although the primary aims of this pilot report were to assess Mind the Gap's feasibility and acceptability, we collected information regarding the intervention's potential effectiveness. Modest improvements were noted in family unit empowerment and autism noesis, while caregiver bureau and stigma remained stable. Farther, the narrowing of reported ranges (i.e., on Family Empowerment Full and Service subscale) at exit indicate that changes on these measures are reasonable post-obit the intervention menstruum, which supports their utilize in a full-calibration trial. The modest sample of this airplane pilot study precluded meaningful analyses of these outcome data; however high rates of survey completion point the feasibility of collecting these outcome information within a larger randomized trial that lends itself to rigorous statistical analyses.

Informing the RCT

The findings from this pilot study informed a big-scale multi-site randomized trial of Mind the Gap, which is currently underway. Parent, coach, and stakeholder feedback from the pilot informed modifications to the intervention for the randomized trial. Commencement, we adult a more flexible arroyo to delivering the intervention that allowed for fewer required in-person visits and more options for telephone-based sessions, in club to decrease the level of burden for coaches and parents. Similarly, we added video chat options for supervision meetings with the research team and parent-coach meetings. We extended the timeline for completion of sessions to reduce burden and allow for flexibility in session delivery. Second, parent and charabanc feedback informed changes to the intervention content, including calculation boosted modules to support families through life stressors outside of the scope of their child's ASD services, such as accessing wellness insurance and addressing food insecurity, as these issues were prevalent among many of the participating families and were often at the forefront of families' concerns. We now consider additional caregiver and autobus characteristics in the matching process for the RCT. Specifically, nosotros enhanced the motorbus interview process to obtain boosted data that was used to develop a matching questionnaire that included new questions about preference for location of peer coach, preferred advice style, and the historic period/gender of the peer coach'southward child. To ensure that peer coaches were sufficiently by the adjustment to diagnosis process for their own kid, we raised the enrollment requirement for the historic period of the coach's child to 9 years. Other changes to the intervention beingness implemented in the current randomized trial include: simplifying data forms, providing additional training to coaches, converting text-heavy information for parents into easily understood infographics, and translating the intervention into Korean to include an even more diverse sample of families in the study.

Limitations

Several limitations are worth noting. First, the study design did not permit for a comparison group, which limits our ability to determine whether the preliminary efficacy outcomes noted were linked directly to intervention. Second, one of the 4 sites did non employ ParentSquare, 1 of our engagement measures, due to local IRB constraints. Although we were able to measure omnipresence in all four sites as a measure of engagement, it would have been preferred to accept the electronic measure of engagement beyond sites. Despite this, the high rates of omnipresence at all four sites, and overall high rates of engagement through the digital platform provide promise for Mind the Gap'southward effectiveness in improving parent engagement. Finally, the high rates of engagement data we observed with Parent Square may have been influenced by the study team'south encouragement for and support of its use, through communication with the coaches. Caregivers may non replicate this level of engagement without ongoing reminders to employ the app,

Determination

There is a disquisitional need for interventions that can exist feasibly implemented and are effective in successfully engaging traditionally under-represented families of children with ASD in their child'southward treatment. Heed the Gap shows promise as an intervention that can exist feasibly implemented with under-resourced and ethnic minority families of children with ASD. The intervention was highly accepted by parents and was implemented with fidelity by lay peer coaches. The community-partnered development process, along with ongoing stakeholder feedback, led to the development of an intervention that is ecologically valid and appropriate for implementation inside nether-resourced customs settings. A rigorous evaluation of Mind the Gap'due south effectiveness at improving parent engagement and service access is currently in process, and a more robust evaluation of RE-AIM within this context will provide information on the intervention'southward potential to be fully implemented.

Availability of information and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the electric current study are not publicly available due to the total trial still beingness underway, but they are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

-

Kasari C, Freeman Due south, Paparella T, Wong C, Kwon Due south, Gulsrud AJCNJoTE. Early intervention on core deficits in autism. 2005.

-

Kasari C, Siller Grand, Huynh LN, Shih West, Swanson Thousand, Hellemann GS, et al. Randomized controlled trial of parental responsiveness intervention for toddlers at high hazard for autism. 2014;37(iv):711-21.

-

Iovannone R, Dunlap Thousand, Huber H, Kincaid D. Effective educational practices for students with autism spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities. 2003;18(3):150–65.

-

DePape A-1000, Lindsay SJQhr. Parents' experiences of caring for a child with autism spectrum disorder. 2015;25(iv):569-83.

-

Brewer AJSS, Medicine. "Nosotros were on our ain": Mothers' experiences navigating the fragmented arrangement of professional care for autism. 2018;215:61-eight.

-

Liptak GS, Benzoni LB, Mruzek DW, Nolan KW, Thingvoll MA, Wade CM, et al. Disparities in diagnosis and access to health services for children with autism: data from the National Survey of Children'due south Health. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics. 2008;29(3):152–lx.

-

Mandell DS, Listerud J, Levy SE, Pinto-Martin JA. Race differences in the age at diagnosis amongst Medicaid-eligible children with autism. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Boyish Psychiatry. 2002;41(12):1447–53.

-

Magaña South, Lopez M, Aguinaga A, Morton H. Access to diagnosis and treatment services amongst Latino children with autism spectrum disorders. Intellectual and developmental disabilities. 2013;51(iii):141–53.

-

Pickard KE, Ingersoll BR. Quality versus quantity: The office of socioeconomic status on parent-reported service cognition, service use, unmet service needs, and barriers to service use. Autism. 2016;20(1):106–xv.

-

Stahmer AC, Vejnoska S, Iadarola South, Straiton D, Segovia FR, Luelmo P, et al. Caregiver Voices: Cross-Cultural Input on Improving Access to Autism Services. 2019:i-22.

-

Howell Eastward, Lauderdale-Littin S, Blacher JJAJoA, Disabilities R. Family impact of children with autism and asperger syndrome: A case for attention and intervention. 2015;1(two):1008.

-

Kuhlthau K, Orlich F, Hall TA, Sikora D, Kovacs EA, Delahaye J, et al. Health-related quality of life in children with autism spectrum disorders: Results from the autism treatment network. 2010;40(6):721-9.

-

Hayes SA, Watson SLJJoa, Disorders D. The impact of parenting stress: A meta-analysis of studies comparison the experience of parenting stress in parents of children with and without autism spectrum disorder. 2013;43(three):629-42.

-

Karst JS, Van Hecke AV. Parent and family impact of autism spectrum disorders: A review and proposed model for intervention evaluation. Clinical child and family psychology review. 2012;15(three):247–77.

-

McStay R, Trembath D, Dissanayake CJCDDR. Raising a kid with autism: A developmental perspective on family adaptation. 2015;2(1):65-83.

-

Grinker RR, Chambers Northward, Njongwe Northward, Lagman AE, Guthrie W, Stronach S, et al. "Communities" in Community Engagement: Lessons Learned From Autism Research in S outh Chiliad orea and S outh A frica. 2012;5(3):201-10.

-

Burkett K, Morris Eastward, Manning-Courtney P, Anthony J, Shambley-Ebron DJJoA, Disorders D. African American families on autism diagnosis and treatment: The influence of culture. 2015;45(10):3244-3254.

-

Maurice C, Mannion K, Letso Southward, Perry LJBIT, Residential Pi, Programs CBC. Parent voices: Difficulty in accessing behavioral intervention for autism; working toward solutions. 2001;16(iii):147-165.

-

Mulligan J, MacCulloch R, Good B, Nicholas DBJSwimh. Transparency, hope, and empowerment: A model for partnering with parents of a child with autism spectrum disorder at diagnosis and beyond. 2012;ten(4):311-330.

-

Tincani One thousand, Travers J, Boutot A. Race, culture, and autism spectrum disorder: Understanding the role of diversity in successful educational interventions. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities. 2009;34(3-4):81–90.

-

Welterlin A, LaRue RHJD, Society. Serving the needs of immigrant families of children with autism. 2007;22(7):747-760.

-

Wellner LJL. Building Parent Trust in the Special Teaching Setting. 2012;41(iv):16-nine.

-

Taylor JL, Hodapp RM, Burke MM, Waitz-Kudla SN, CJJoa R. disorders d. Grooming parents of youth with autism spectrum disorder to advocate for adult disability services: Results from a airplane pilot randomized controlled. trial. 2017;47(iii):846–57.

-

Magaña Due south, Lopez K, Machalicek Due west. Parents Taking Activity: A Psycho-Educational Intervention for Latino Parents of Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder. Family process. 2015.

-

Magaña South, Lopez K, de Sayu RP, Miranda E. Use of promotoras de salud in interventions with Latino families of children with IDD. International Review of Inquiry in Developmental Disabilities. 47: Elsevier; 2014. p. 39-75.

-

Magaña S, Lopez Grand, Machalicek WJFp. Parents taking activeness: A psycho-educational intervention for Latino parents of children with autism spectrum disorder. 2017;56(ane):59-74.

-

Pellecchia G, Nuske HJ, Straiton D, Hassrick EM, Gulsrud A, Iadarola S, et al. Strategies to engage underrepresented parents in kid intervention services: A review of effectiveness and co-occurring use. 2018;27(10):3141-54.

-

Holkup PA, Tripp-Reimer T, Salois EM, Weinert CJAAins. Customs-based participatory research: an arroyo to intervention inquiry with a Native American customs. 2004;27(3):162.

-

Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SMJAjoph. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. 1999;89(9):1322-7.

-

Glasgow RE, Klesges LM, Dzewaltowski DA, Bull SS, Estabrooks PJAoBM. The hereafter of health behavior modify research: what is needed to improve translation of research into wellness promotion practice? 2004;27(i):iii-12.

-

Kuhn JC, Carter ASJAJoO. Maternal self-efficacy and associated parenting cognitions among mothers of children with autism. 2006;76(iv):564-575.

-

Firpo YMD, A.; Garcia, Grand.; Caveleri, M.A., McKay, Grand., Chavira, D.A. Psychometric Properties of a Parent-Reported Mental Health Stigma Scale. . Western Psychological Clan Convention; Burlingame, CA2012.

-

Koren PE, DeChillo North, Friesen BJJRp. Measuring empowerment in families whose children have emotional disabilities: a brief questionnaire. 1992;37(4):305.

-

Graves KN, Shelton TLJJoC, Studies F. Family empowerment as a mediator between family-centered systems of care and changes in child functioning: Identifying an of import mechanism of alter. 2007;16(four):556-66.

-

Cooper BR, Bumbarger BK, Moore JEJPS. Sustaining evidence-based prevention programs: Correlates in a large-scale dissemination initiative. 2015;xvi(i):145-57.

-

Fortuna KL, DiMilia PR, Lohman MC, Bruce ML, Zubritsky CD, Halaby MR, et al. Feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary effectiveness of a peer-delivered and technology supported self-management intervention for older adults with serious mental illness. 2018;89(two):293-305.

Acknowledgements

We would like to give thanks our community collaborators for back up in the development of Heed the Gap. Los Angeles: Fiesta Educativa; Healthy African American Families; Los Angeles Unified School District; Due south Central Los Angeles Regional Eye; The Spectrum of Hope Foundation; Westside Regional Heart. Sacramento: Alta Regional Center; UC Davis Center for Excellence in Developmental Disabilities & LEND programs; California State University, Sacramento; California Department of Developmental Services; Family Resource Network; Family unit Soup Resource Center; Help Me Grow – Yolo County; North Bay Regional Center; Sacramento County Office of Education; Sacramento County, Section of Health & Human Services, Segmentation of Public Wellness (MCAH); Solano County Office of Education; Warmline Family Resource Center; Yolo Early Start (Yeah) Team. Philadelphia: Elwyn. Rochester: Common Footing Health; Mary Cariola Children's Centre; Livingston-Wyoming ARC; Rochester Association for the Pedagogy of Immature Children; Rochester Urban center School District; Roosevelt Children's Centre; Starbridge; Potent Heart for Developmental Disabilities. In addition, we are extremely grateful to the families who participated in the study and the peer coaches who provided their expertise and compassion to this projection.

Funding

Funding Information: This study was funded by the Health Resources Services Administration (HRSA) award number UA3 MC11055 HRSA PI: Kasari.

Writer information

Affiliations

Contributions

SI participated in intervention design and development; led local recruitment, data collection, and supervision of study procedures; wrote parts of the manuscript. MP participated in intervention design and evolution; led local recruitment, information drove, and supervision of study procedures; wrote parts of the manuscript. HSL contributed to intervention development; supervised aspects of study procedures; conducted information analysis; wrote parts of the manuscript. LH conducted data analysis; wrote parts of the manuscript. EMH contributed to study design; led all aspects of technology-related information collection, analysis, and interpretation; wrote parts of the manuscript. SC contributed to intervention evolution; supervised aspects of study procedures; conducted data analysis; wrote parts of the manuscript. SV contributed to intervention development; supervised aspects of report procedures; conducted data analysis; wrote parts of the manuscript. EM contributed to intervention development; supervised aspects of report procedures; conducted data analysis; wrote parts of the manuscript. HN contributed to intervention development; supervised aspects of study procedures; conducted information assay; wrote parts of the manuscript. PL contributed to intervention development; supervised aspects of study procedures; conducted data assay; wrote parts of the manuscript. CF supported data collection, analysis, and interpretation related to technology data; wrote parts of the manuscript. AG contributed to study blueprint; intervention development; led local report procedures; conducted data analysis; provided review and editing of the manuscript. DM contributed to study design; intervention development; led and supervised local study procedures; provided review and editing of the manuscript. CK contributed to written report design; intervention development; led and supervised local written report procedures; provided review and editing of the manuscript.

AS led report design; intervention development; led and supervised local study procedures; provided last review and editing of the manuscript. The writer(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors' data

Dr. Tristram Smith passed abroad prior to the publication of this manuscript. His significant intellectual contributions and content expertise were critical to the execution of this projection and are reflected in the findings of our AIR-B network.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics blessing and consent to participate

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the University of California, Los Angeles, University of California, Davis, University of Pennsylvania, Drexel Academy, and Academy of Rochester institutional research boards. UCLA served as the IRB of record (IRB# 17-000029). Informed consent was provided by all study participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they take no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in whatsoever medium or format, every bit long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(south) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Eatables licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other 3rd party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If textile is not included in the article's Creative Eatables licence and your intended use is non permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you lot will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/4.0/. The Creative Eatables Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zip/1.0/) applies to the information made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and Permissions

Near this commodity

Cite this article

Iadarola, Southward., Pellecchia, M., Stahmer, A. et al. Mind the gap: an intervention to support caregivers with a new autism spectrum disorder diagnosis is feasible and acceptable. Pilot Feasibility Stud half dozen, 124 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40814-020-00662-6

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40814-020-00662-6

Keywords

- Autism spectrum disorder

- service access

- disparities

- caregiver education

Source: https://pilotfeasibilitystudies.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40814-020-00662-6